The term ‘vulture’ has gained numerous negative connotations in our language. The idea of feeding on the dead is abhorrent to humans, and so our modern vernacular has demonized them to an extent. In fact, the second definition of ‘vulture’ in the dictionary is “a contemptible person who preys on or exploits others.” However, some earlier cultures actually venerated vultures and I think that much more appropriate, as they provide a vital ecological service.

Here in Florida, we have two different species of vulture: the American black vulture, Coragyps atratus, and the turkey vulture, Cathartes aura. The latter is also frequently referred to as a ‘buzzard’. Both of these species are part of the New World Vultures, a family of seven living species that includes North and South American vultures and condors. While similar in appearance, genetic studies have shown that they are not directly related to the Old World Vultures of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Their shared appearance and ecological niches are a result of convergent evolution, the tendency of similar environmental circumstances leading to similar adaptations in unrelated organisms.

As you are likely aware from seeing them, and the title of this particular newsletter, vultures primarily feed on carrion. Both of our Florida vultures don’t have beaks or talons that are sharp enough to reliably kill prey. Instead, they are able to travel over long distances to find a carcass using thermals, natural updrafts created by warm air hitting the ground and rising. Vultures will sometimes ride these thermals in large groups known as ‘kettles’. They can locate a carcass using sight, but also using an interesting combination of adaptations.

More recent scientific studies are showing that the lack of a sense of smell in birds may have been exaggerated, but regardless of this, the turkey vulture in particular has a large and highly-developed olfactory lobe of the brain. This allows them to detect the presence of a decaying animal by picking up on the scent of ethyl mercaptan. This gas is one of the components that makes rotting carcasses stink and is added to normally odorless fuels like propane and butane to make it easier to notice leaks.

The black vulture, on the other hand, as well as several other species, does not possess this improved sense of smell. Instead, it has adapted by learning to follow turkey vultures to a fresh carcass. If they succeed, they can chase off the turkey vulture if they want, as they tend to forage in groups while turkey vultures are usually solitary. Both these species, in fact all seven New World vultures, possess a distinctive ‘bald’ or featherless head, a feature that is not present in several species Old World vulture. This adaptation is a measure to improve cleanliness. Since they feed on decaying flesh, their heads are likely to get messy. Not having feathers there means not having to clean or preen them and reduces the risk of infection.

Decaying bodies are an excellent breeding ground for dangerous bacteria and this is at the heart of the important role vultures and other scavengers provide to an ecosystem. Eating rotting flesh reduces waste and ‘recycles’ back into the system and helps prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

So, how does one go about determining which vulture species you’re looking at? At first glance, it might seem relatively simple; the black vulture has a grey or black head while the turkey vulture’s head is more reddish-pink. However, spotting this can be challenging if you aren’t close up, and almost impossible if the bird is flying. Thankfully, there are some other differences between them. As you can see in the photo above, turkey vultures have an entire line of underwing feathers that are white or gray. Black vultures only have lighter colored feathers at the wingtips, as shown below. And what if you are seeing them from a distance and not underneath? Turkey vultures are known for not flying with their wings straight out but rather taking the shape of a shallow V, which sets them apart from many other birds and not just the black vulture.

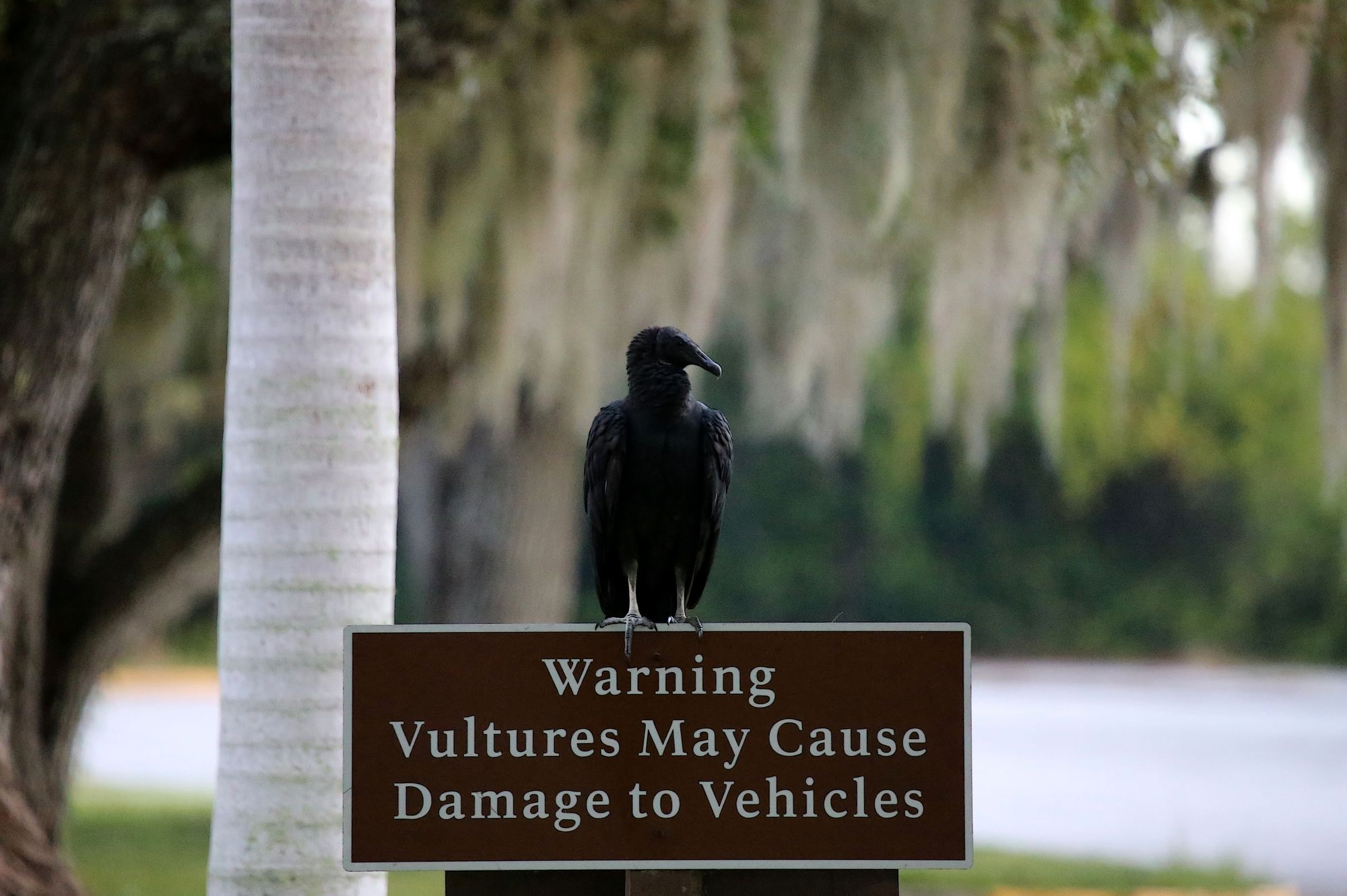

Of course, whenever an animal comes in contact with human systems, their behavior can shift. Like other animals, vultures have discovered the treasure trove that is human garbage. Roadkill is also an excellent source of easy food for them. As they spend more time around people, some vultures have started to become a nuisance. I have heard anecdotal examples of vultures, particularly black vultures, tearing into screen of doors or porches and tearing the rubber off of windshield wipers. Their excretions can be corrosive in large quantities and some localities have developed anti-vulture deterrents such as spikes on top of light poles to dissuade the birds from landing there.

However, regardless of how much of a nuisance they might occasionally make of themselves, vultures should be appreciated for their important role as a piece in nature’s clean-up crew. In ancient Egypt, they were seen as a symbol of both death and rebirth. They are also present in a variety of Mayan and Aztec legends. And even if you don’t like them, I imagine you’d like a proliferation of rotting corpses even less.