Mangroves are a group of tree species that inhabit coastal areas in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. They are known for being highly salt tolerant and well-adapted for the harsh conditions of the coastal environment.

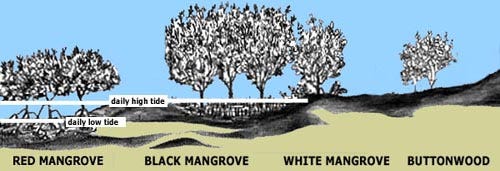

Florida is home to three mangrove species: the red mangrove, Rhizophora mangle, the black mangrove, Avicennia germinans, and the white mangrove, Laguncularia racemosa. The mangrove forests of Florida exist on a gradient of salt tolerance. The most highly tolerant red mangrove is the closest to the open ocean, followed by the slightly less tolerant black mangrove and then the even less tolerant white mangrove. The species do overlap, but overall tend to place themselves similarly to the diagram below.

The buttonwood, Conocarpus erectus, is another typical species found even farther inland than mangroves but commonly associated with them. Of course, even though some Florida mangroves are less tolerant of saline conditions than others, it is important to remember that most plants could not survive at all in these conditions. A high concentration of salt on the outside of a normal plant cell will draw water out of it, causing the cell to shrivel. Mangroves get around this with a variety of methods including exclusion (preventing the salt from being absorbed) and secretion (expelling excess salt from the plant).

However, at the end of my last story, I mentioned that the mangroves of Florida were an example of the consequences of removing a species from an important system. Mangroves were cleared from many coastal areas of Florida in order to make room for development and construction. This helped fuel economic growth and a steady influx of people. However, the elimination of mangroves had some unintended consequences.

For one thing, the habitat created by the mangroves’ unique root system provides an excellent nursery for a wide variety of marine life, including various species of fish and crustaceans. Negative impacts on the populations of these species are not just ecological, either. Many of these species have economic value themselves, either commercially or as sportfish.

If a nursery were all that mangroves provide, their economic value for the state would already reach the millions of dollars. However, much like other types of wetlands, they can also improve water quality by filtering or removing toxins or excess nutrients. In addition, they can create a natural buffer against severe weather. Prior to Hurricane Matthew this year, it had been over ten years since a major, destructive hurricane had made landfall in Florida. However, the first decade of the 21st century saw an unusually high number of hurricanes for the state and mangroves further proved there importance.

Hurricanes wreak havoc in two ways: wind and water. The root structure of mangroves allows them to survive the former and mitigate the latter for locations inland. Flooding and storm surge can be just as costly in lives and destruction as hurricane force winds. Within the last few decades, we have begun to realize just how important mangroves are for preventing water inundation of this nature.

Thankfully, the overall loss of mangrove habitat for Florida for the period of the 20th century is estimated at only about 5%. However, this is not evenly spread and certain areas, Tampa Bay for example, have lost half or more of their mangroves. There are now regulations regarding the maintenance of mangrove trees in Florida. They can be trimmed in certain ways, but cannot be removed without a permit. This is because the state has recognized the ecological and economic value of these plants and the habitat they create.

Unlike some of the species I have featured in my stories, the three mangroves of Florida are not threatened with extinction. However, careless removal of these plants can have major unforeseen impacts. As you go about your day, I would like you to think about a species that you find personally annoying or have at one point or another wished did not exist (please exclude non-native introduced species from this thought experiment). Then, I want you to think about the connections I mentioned in my previous story. ‘No man is an island,’ and no species is either. Would you be so willing to disrupt the system and sever those connections if you could see all the consequences beforehand? Perhaps, or perhaps not. Maybe eliminating a particular pest will be worth the unintended consequences, but at the least you should not discount the possibility that it will not.