This week, we’re leaving the occasionally complicated world of commensalism and shifting focus to parasitism. Before we get to this week’s story, I’m going to go over a few things to clarify what parasitism is, and what it isn’t. If you recall the summary story at the start of this season, you might remember that each of the three types of symbiosis we’re talking about can be abbreviated with symbols indicating the overall effect on each participant. Parasitism is abbreviated as ‘+ -’, meaning that one organism benefits to the detriment of another.

However, not every interaction that involves such outcomes qualifies as parasitism. A predator is not a parasite of its prey. In order to qualify as parasitic symbiosis, the two species must exist closely together for an extended period of time. Furthermore, while many parasites cause disease in their hosts, viruses do not count. While there is some debate in the scientific community, the general consensus is that viruses do not qualify as life. A virus is simply a strand of genetic material (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a protein coat. They do not have cells or an independent metabolism, two characteristics required of living things. Thus, while the relationship between a virus and its host is similar to that of a parasite, it is not considered an example of symbiosis (at least for our purposes in these stories).

Parasitism can be less complicated than commensalism. This is partially because of the ongoing debate about the validity of commensalism that I mentioned in my introduction to it. Also, much like mutualism, it is easier to understand parasitism in an evolutionary context. While mutualism fuels evolution by creating a kind of feedback loop where the two organisms gain more benefits the closer they associate with one another, parasitism involves a kind of evolutionary competition. This is also seen in predator/prey relationships and often referred to as an ‘evolutionary arms race’. This means that the host is constantly developing ways to prevent the detrimental effects of the parasite and the parasite must then develop new ways to overcome these countermeasures.

There are a variety of different types of parasitism. For the first two stories, we’re going to focus on two categories based on the location of the parasite. The first of these will be on endoparasites. An endoparasite exists inside of the host body, either within its cells or in the space between cells. Thus, most endoparasites tend to be small and many are single-celled organisms.

However, this is not always the case. Tapeworms, a group of flatworms that live in vertebrate digestive systems, can grow to 20 or even 30 meters long in larger animals. These worms (not closely related to the earthworms you are likely more familiar with) attach to the host intestine using a specialized structure called a scolex (seen below) and extract nutrients from the host in this manner. All vertebrates can be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm (there are several common to humans, usually contracted by eating undercooked meat, with a different species of tapeworm found in beef, pork, and fish).

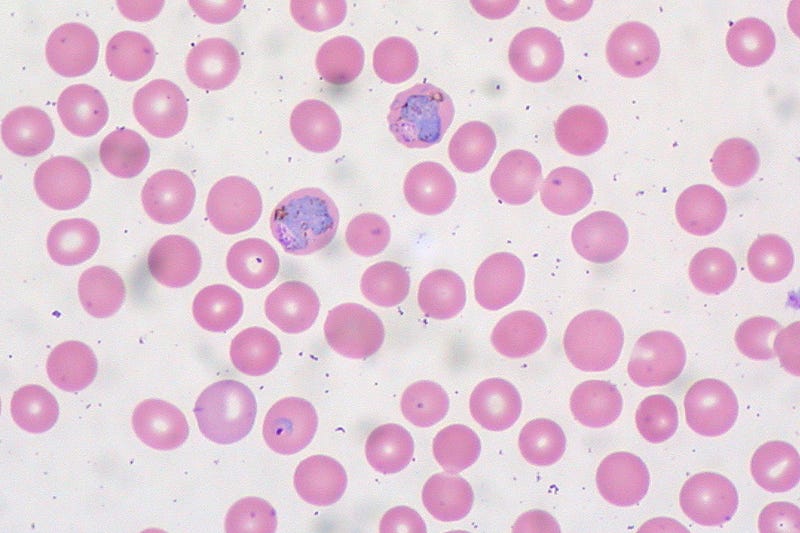

Some parasites require a more direct animal vector in order to infect their hosts. One of the most famous of these is the genus Plasmodium, a single-celled organism which uses a mosquito host vector and causes the disease known as malaria. These parasites live inside human red blood cells, as seen below.

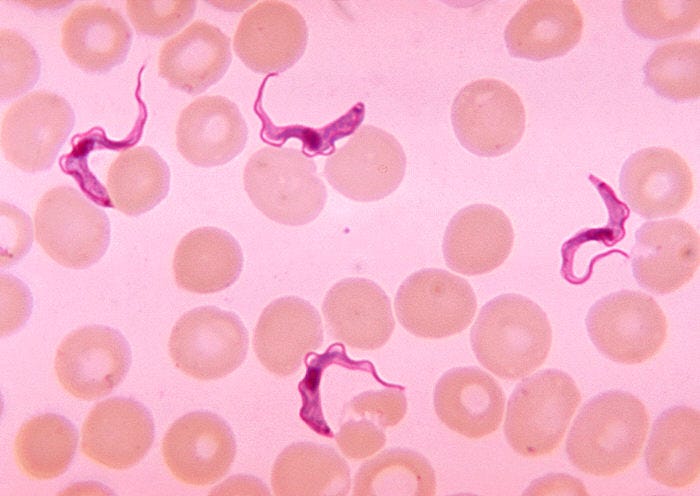

Similarly, single-celled organisms of the genus Trypanosoma are transmitted through certain fly species and cause human diseases known as sleeping sickness and Chagas disease. Like the malaria parasite, the infection takes place in the blood, but the organisms do not enter the blood cells.

One of the most interesting endoparasites, at least in my opinion, is not a human parasite, but instead mainly parasitises insects and similar arthropod species. The interesting part about these parasites is that they are actually fungi, belonging to the genus Cordyceps. The spores of the fungus are released into the air and, if they come in contact with a host, infect its body, slowly replacing its internal structure with fungal tissue. Eventually, fruiting bodies sprout from the dead host insect (as seen below) and release more spores, spreading the fungus further. Some species of this fungus can even alter the behavior of their hosts in order to optimize the environment for this release of spores

There are even endoparasitic plants. Species in the genus Rafflesia, native to southeast Asia, exist almost entirely inside the tissues of its host plant, a type of vine. The only part that can be seen externally is the large flower (12 to 100 centimeters in diameter depending on species). These flowers have developed a unique way to attract their pollinators. They look and smell like rotting flesh, which attracts flies and other insect pollinators and has given it the nickname ‘corpse flower’.

Of course, there are so many different types of endoparasites (including nematodes, flukes, pinworms, hookworms and a wide variety of protozoans) it would be impossible to include them all in this one story, but I hope you found these few examples interesting. Next week we’ll be moving outside the host body and talking about ectoparasites, those that live separately from their hosts.