Of course, when I heard questions about how Hurricane Ian affected wildlife in the area, the vast majority of people were interested in the local animal populations, particularly birds. I can certainly understand and relate to such interest. My own research background is rooted in the study of animal behavior. But, like with dinner, you can’t have dessert until you eat your veggies.

Before we start discussing the various types of animals and hurricane impacts on them, we should look at the effect of these storms on plants. Everything in an ecosystem is connected, so several of the storm consequences to flora we talk about now will come up again when we’re discussing fauna instead. We’ll start with a look at various different types of trees.

Trees probably provide one of the more dramatic demonstrations of hurricane-force winds. As the aphorism goes, we cannot see the wind, but we can know it exists because we can observe its effects on other things. In addition to that, fallen trees or limbs can cause power outages or block roads, so we tend to notice them more. Large trees have much more surface area for the wind to act on and so are more vulnerable than other types of plants to that particular hurricane hazard.

Last time, we talked about three major categories of hurricane damage: wind, waves and surges, and rain and flooding. As we proceed, we’ll look at how the different organisms deal with each of these factors.

Palms

Palm trees are the stereotypical Florida plant, we have 12 native species of them, and watching them sway in high winds is both fascinating and a bit frightening. How do palms deal with a hurricane?

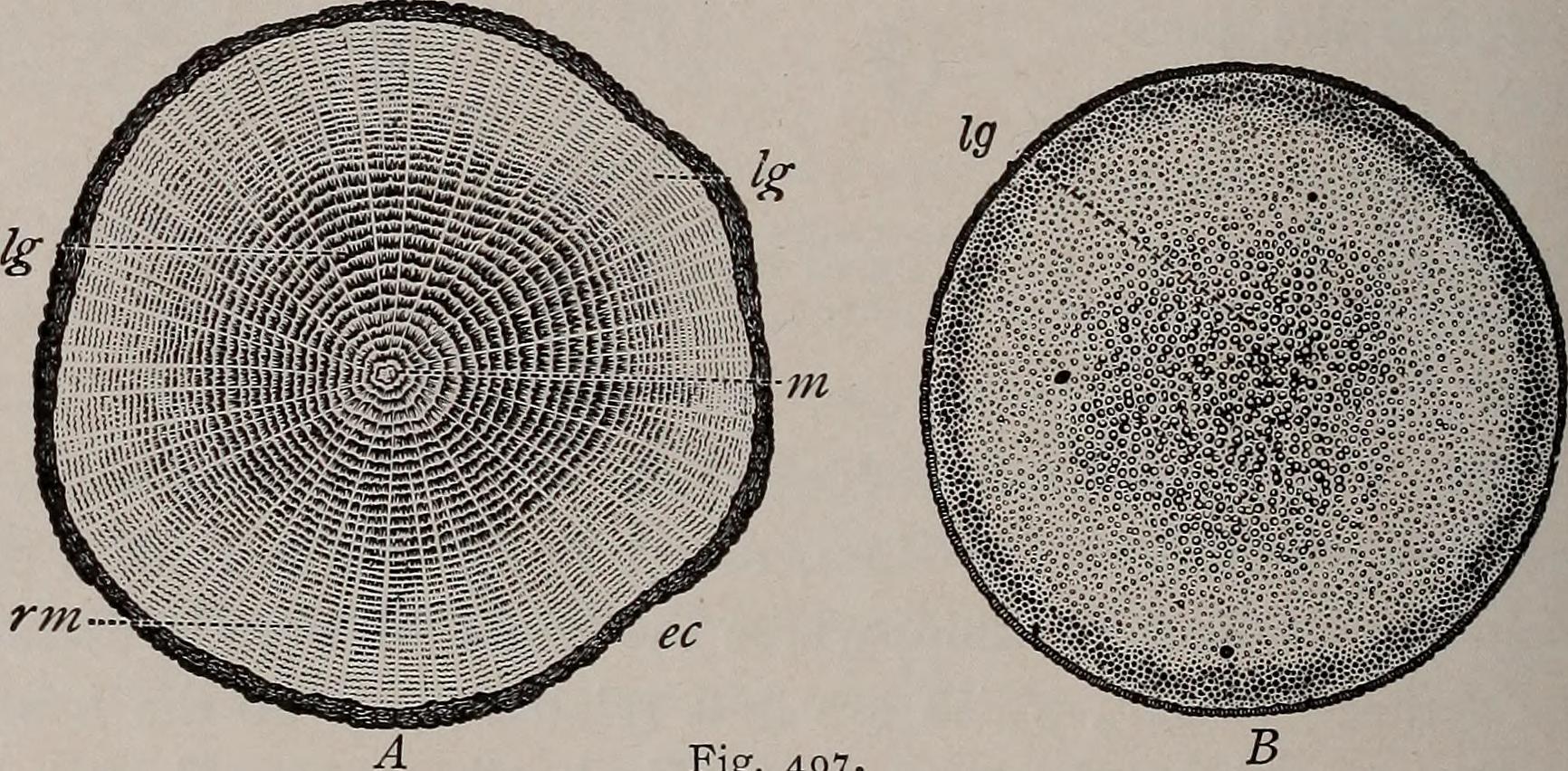

It is less likely for a palm tree to be knocked over by wind. This is due to a structural difference between them and most other trees. When the trunk of most trees is looked at in cross section, you can see visible rings as the tree grows laterally each year. Palms do not have the ability to increase the width of their stems using the method that produces such rings. Instead, their wood grows in bundles in the interior of the stem. Below, you can see cross sections of an oak tree on the left and a palm on the right.

Because of this difference in structure, the tissues of palms resemble grasses much more than trees, unsurprising as both groups are monocot plants while most trees are dicots (some botanists don’t even call palms ‘trees’ at all). This gives them a spongy and springy texture and the ability to bend much more than most trees. Therefore, a palm usually won’t snap in half from the wind, even in a hurricane.

Palm fronds are not quite as resilient and after Ian, the ground was littered with them. But, for a native Floridian, this isn’t all that unusual a sight. Fronds fall off naturally over time and tree maintenance crews can be seen removing dead fronds early for safety reasons (some palm species have rather large fronds that can cause severe injury if they land on someone). Losing fronds early due to hurricane winds won’t hurt an individual tree, as it can grow more from its apical bud at the top. This is the true ‘heart’ of a palm tree and it can continue on as long as that is intact.

But what about water? This can be much more of a threat. Palm trees on the beach can be swamped by storm surge. This can undermine their root structure and topple a tree that could survive the wind alone. As for flooding, the level of tolerance will vary between species. However, palms generally prefer well-drained soil. This means that the soil conditions they grow in will likely allow for adequate drainage of floodwaters prior to experiencing a negative reaction. However, it also means abnormally large and long-lasting flooding can harm the plant, as they aren’t adapted to being underwater for extended periods.

Live Oak

The southern live oak, Quercus virginiana, is a common tree in both landscaping and natural forests throughout the southeastern United States. Without doubt, Hurricane Ian did some of the most dramatic damage to this species in terms of the sheer amount of fallen tree limbs. Below, you can see an aftermath photo taken just below my own living room window.

In direct contrast to palm trees, I’m not sure if I can personally think of a species more susceptible to wind damage than the live oak. While palms grow straight up, live oaks have a tendency to branch and twist in multiple directions, increasing their surface area. Also, live oak wood is incredibly dense. It was used for the hulls of wooden ships back in the day and some such vessels even had cannonballs bounce off their oak sides during battle (this property is how the famous USS Constitution got the nickname ‘Old Ironsides’). This means that individual branches are quite heavy and more likely to fall if they are damaged in heavy wind. However, live oaks have a deep taproot and widespread overall root system. This means that while most trees will lose limbs in a hurricane, the tree itself will usually remain upright.

Live oaks are an upland species and aren’t likely to be located near potential storm surge areas, though any that are can usually manage with the force of water for the the same reason it can survive heavy winds. While they can’t remain submerged for extended periods, live oaks are also relatively flood tolerant in the short term.

Cypress

Bald cypress, Taxodium distichum, is a fascinating species. A non-evergreen conifer, they can be found throughout Florida, up the Atlantic coast to New Jersey, along the Gulf shore into eastern Texas, and north through the Mississippi River valley until southern Missouri and Illinois.

The main trunk of a cypress tree isn’t particularly well-suited for high winds, but the branches are much smaller and thinner than some other trees, so they are less likely to fall from their own weight. Cypress trees may also derive increased stability from the cypress knee structures that form vertically from the tree’s roots. Another post-Ian photo of mine below shows a bent bald cypress, indicating potential vulnerability, but also resiliency.

Water is not a major concern for these trees. The bald cypress is an important wetland species here in Florida, to the extent that it even forms part of the name of multiple different types of wetlands we find here (e.g. cypress dome, cypress slough). It regularly spends months at a time fully submerged in water, so even catastrophic flooding caused by hurricane rains would not bother them. However, their one major potential vulnerability is their salt tolerance (or rather, lack thereof). They are not a beach species, but can be found on riverbanks, so may receive an increase in salt content as storm surge travels upriver.

Pines

Sometimes, even I forget how diverse Florida’s pine forests can be. We actually have seven native species of pine tree, but only one can be found in Southwest Florida, where I live. That’s the slash pine, Pinus elliottii, so named for the V-shaped slashes made to collect the sap for processing into turpentine.

As conifers, pine trees are somewhat similar to the aforementioned bald cypress. The major difference being that they are primarily an upland species, preferring slightly drier conditions. Reviews of pine forests after major hurricanes have shown that mortality is relatively low, mainly found in larger individuals and often associated with clusters of larger trees. This means that nearby trees can contribute to a negative outcome, but more than 3/4 of the adult trees in an area will remain standing.

Contrast this with the Australian pine, which, despite the name, is not a pine tree at all but a flowering plant in the genus Casuarina. This tree was brought over and planted here in Florida because of the exceptionally deep taproot it grows in its native habitat. People believed that this would be a very stable species. However, they failed to take into account the reasons for its physiology. It is native to areas of Australia that can be semi-arid, requiring a deep root in order to access water. The much wetter conditions of Florida meant these trees did not need to grow down deep to reach moisture. As a result, they are actually incredibly unstable and tend to topple in high winds.

As mentioned before, pine trees do not experience periodic flooding like the bald cypress, but they are often found in soils with relatively poor drainage. This means that if flooding occurs from a hurricane, it may take some time for it to recede, but the trees are able to handle a short period of flooding. Their salt tolerance is of slightly less concern simply because of their usual growing areas being away from beaches and estuaries. However, pine trees on barrier islands can experience a high mortality rate from salt inundation.

Mangroves

There are three species of mangroves that can be encountered in the coastal areas of Florida. They are incredibly important for a number of reasons, including as a nursery for many marine and estuarine species.

By their nature, mangrove trees are already flood and salt tolerant. The extent of this varies with species, to the point where you can often see a progression in Florida mangrove forests from one type to another (from white mangrove to black mangrove to red mangrove) as you get closer to the ocean with more constant inundation and higher salinity. This means that these trees are some of the most resilient to storm surge and increased salt content. As they are coastal, they are unlikely to experience flooding from rain.

Unfortunately, mangrove forests are quite vulnerable to high winds. Mangroves can take heavy damage from hurricane winds, and while they are resilient, it can become a problem if they are also under stress from other sources such as encroaching development.

One of the most interesting factors in the severity of hurricane damage is the ability of mangroves to mitigate that damage to other areas. They are able to contain storm surge and thus reduce coastal flooding. Thus, high mangrove concentrations actual increase the survival of other native species in a hurricane.

Conclusions

Likely, you are able to see a pattern emerging from the above examples. Each type of tree has its own strengths and weaknesses in relation to hurricane impacts. A single species will rarely be immune to all of them, but is usually able to find a way to mitigate the problems associated with their vulnerabilities.

Unlike animals, plants aren’t able to ‘get out of the way’ of a hurricane. They just have to stay there and take it. Because hurricanes are a regular event here, the native plants have had a long time to adapt to the hardships such storms represent. It is an excellent example of evolution through natural selection. A major storm might wipe out some individuals, perhaps even a large number of them, but the survivors will be able to pass down any traits that helped them to future generations.

This is going to be a reoccurring theme throughout this season of Nature Stories. Humans have a tendency to view things through individual eyes. It’s how our internal thoughts work and thus is easier for us to process. However, evolutionary biology does not function on the individual level, only on larger groupings called populations.

Next time on ‘Winds of Change’, we’ll look at how some other kinds of plants handle a hurricane.