We’re staying in an aquatic environment this week, but moving away from the ocean again. Instead, we’ll be looking at some of the only bioluminescent organisms native to freshwater habitats. Specifically, a group of freshwater snails. We’ve discussed snails a few times previously in both terrestrial and marine environments. The genus Latia consists of three living species (and an additional fossil species now extinct) of snails. They all attach themselves to rocks in running streams or rivers and can only by found in New Zealand on the North Island.

These snails are commonly called ‘limpets’, although they are not taxonomically related (at least not closely) to the true limpets, which are all marine species. However, they do resemble them in that both possess a conical-shaped shell with little to no sign of spiraling. They also both attach themselves to rocks and feed off of algae and other organisms that make up the surface film of that habitat. Below, you can see both the top and underside view of a true limpet. They are able to maintain a grip on their rocky habitat thanks to their ‘teeth’, which are the strongest known biological material (their tensile strength is even higher than spider silk).

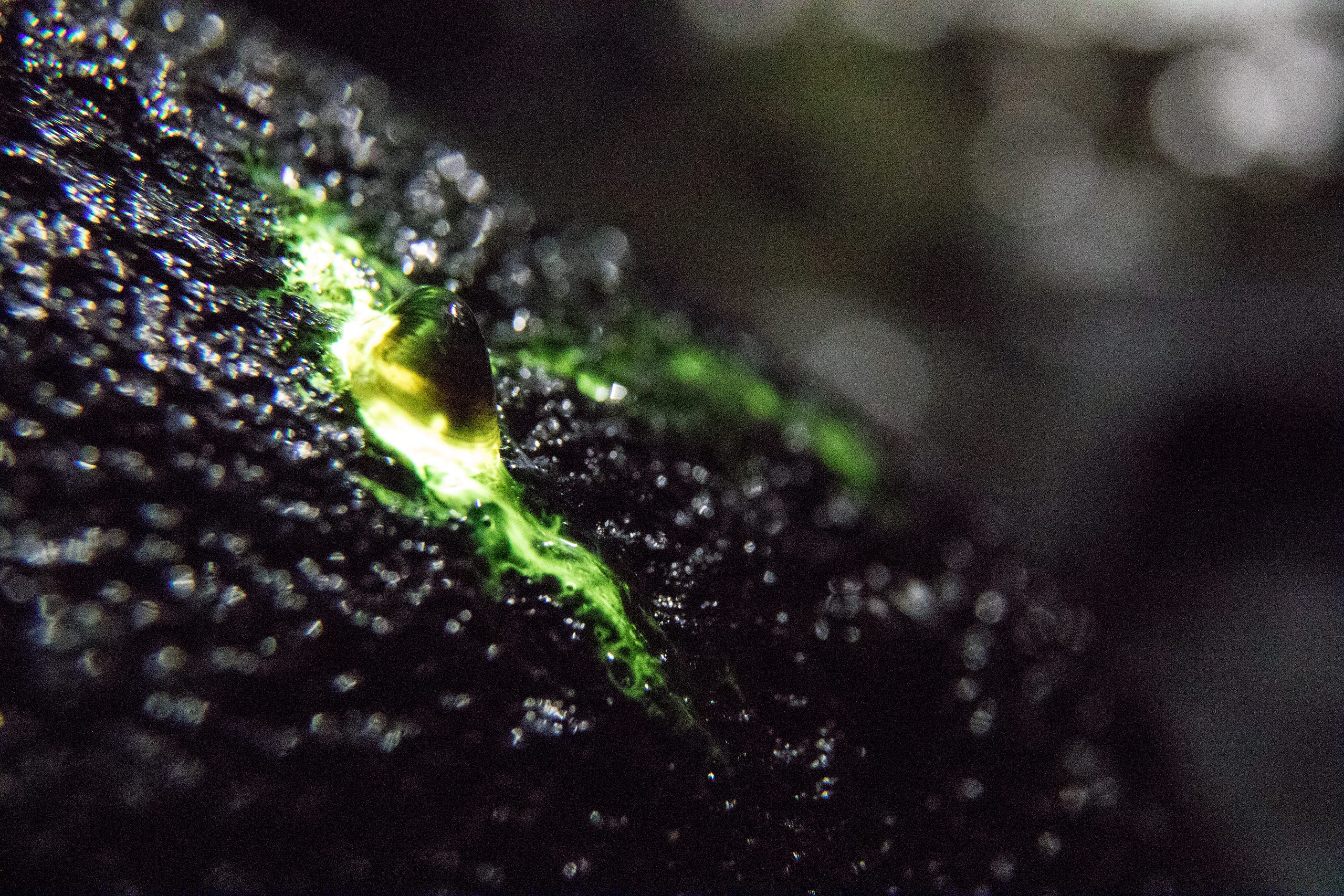

What makes the three Latia species unique, besides their limited distribution to freshwater rivers and streams on a single island, is that of the approximately 4,000 species of freshwater snails, they are the only ones that exhibit bioluminescence. In addition, the form that this illumination takes is quite different from the previous organisms detailed so far this season. In those previous examples, the chemical reaction that produced the light occurred inside part of the organism. As can be seen in the top picture, these snails secrete a glowing slimy substance when disturbed. The bioluminescence does not remain contained within these snails, but is instead expelled onto the surrounding area.

The exact mechanism of action for this process is still not fully understood, nor is its purpose, though it is presumed to be some form of defense mechanism. Possible hypotheses include its use as a distraction against predators, drawing them towards the light instead of the snail (similar in some respects to how some species of lizards can drop their tails, leaving them behind for a predator while the lizard escapes). It is also possible that the bioluminescent slime can cling to a predator, confusing it, or drawing attention to it for other, larger predators.

Interestingly enough, the secretion does not necessarily require a physical disturbance. The snails can also detect slight chemical changes in the water and will react to them. This response could, theoretically at least, be used for water quality assessment purposes, although its effectiveness in such a regard is somewhat questionable.

Much like many of the other stories shared so far for Season 8, Latia snails are not an organism you are likely to ever see, though this is due more to their remote geography as opposed to occupancy of the deep ocean. However, there are plenty of bioluminescent organisms that you can observe and enjoy locally. Fireflies of varying types are one of these. The next time you see a swarm of glowing motes hovering around, think back to some of the other examples we’ve shared so far and how fascinating they truly are.

As always, I hope you are enjoying my writing and this season’s topic. Please like and share if you do. I am also always interested in comments on how to improve and topic suggestions for future seasons.