This tree is likely familiar to a good portion of my readers, especially those who live in Canada and the NE United States. It is the paper or canoe birch, Betula papyrifera, and its peeling bark is a common sight in the forests of northern North America. This species can’t possibly be Threatened with extinction, right? Correct, but a close relative of it is. In fact, there is only one known specimen left.

The species is known as Betula szaferi (there is no common name) and it was a birch tree found only in Poland. There are no wild populations of this species anymore. The only remaining individual can be found planted in the Kraków Botanical Garden. Because of this, Betula szaferi is classified as Extinct in the Wild, a category reserved only for species that remain in captivity or cultivation with no wild individuals. It is not known exactly when the complete extinction of wild populations took place, but it occurred sometime before 1998, when surveys found no more wild plants.

Extinct in the Wild is a slightly odd classification. Not all Extinct species qualify for it before they disappear. Most often, a species gains this description because people saw the possible extinction coming and began captive breeding programs in an effort to save the organism. Sometimes, a species can be reintroduced after becoming Extinct in the Wild. Such reintroduction does not always succeed, but there are examples of species that again have wild populations such as the red wolf, Canis rufus, and the Arabian oryx, Oryx leucoryx (though these species are still classified as one of the Threatened categories).

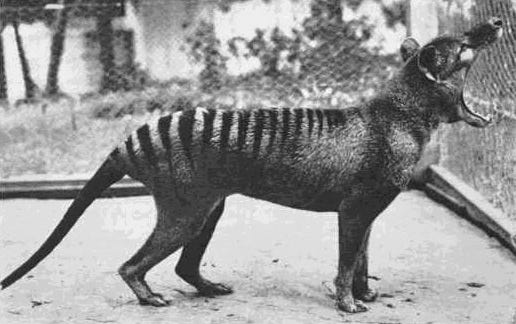

One of the most famous species to ever be named Extinct in the Wild is the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger, Thylacnius cynocephalus, a carnivorous marsupial with striped hindquarters native to Australia and Tasmania. It became extinct on mainland Australia approximately 2,000 years ago but continued to survive on the island of Tasmania. It was blamed for attacking livestock and hunted to the brink of extinction (though disease and competition from introduced feral dogs also played a role). The last known thylacine, seen below, was captured in 1933 and brought to the Hobart Zoo. It died in 1936. Since then, there have been numerous supposed sightings of thylacines in the wild. None have been verified and they are likely either cases of mistaken identity or outright fraudulent.

For Betula szaferi, no efforts are currently being made at reintroduction, though there is some possibility for reconstructing its genetic diversity because of an interesting quirk of the birch genus. Plants in the genus Betula will freely hybridize with one another if conditions allow it. This means that different species can create fertile offspring when they reproduce. Because of this, there is still disagreement among botanists about how many individual birch species actually exist (ranging from under 30 to over 60). Before it became Extinct in the Wild, Betula szaferi is known to have hybridized with the related, and much more common, silver birch, Betula pendula. This species, seen below, is widespread throughout Europe and northern Asia. It is also considered an invasive pest in some parts of North America where it has been introduced.

The result of this hybridization is Betula oycoviensis, a tree that can be found in 8 northern European countries, usually on the margins of forests where its two parent species once coexisted. There are some that do not consider it a separate species, but merely a variety of Betula pendula. The hybrid itself is under some threat, mainly due to habitat loss, and could be considered Vulnerable if it is indeed a separate species.

Unfortunately, the truth of the matter is that once a species has reached the level of Extinct in the Wild, the chances of long-term survival are slim. Genetic diversity is often reduced and the level of inbreeding increased. Reintroduction back into the wild requires that the problems that caused the species to reach this level of threat be dealt with first. Such is the case for the Panamanian golden frog, Atelopus zeteki, which cannot be reintroduced until the fungal infection known as chytridiomycosis, which has been decimating amphibian populations worldwide for over two decades, can be brought under control.

For a species like Betula szaferi, for which only one specimen remains, it is much more likely to follow in the footsteps of Lonesome George, the last known Pinta Island tortoise, Chelonoidis abingdonii, who died in captivity five years ago after years of unsuccessful attempts at breeding with a closely related species. I was fortunate enough to get a chance to see him during my trip to the Galápagos I mentioned in one of my first stories.

I hope you are all finding this trip through the different aspects of Threatened species as interesting as I am. For next week, we’ll finally look at the end stage that all of the current conservation efforts are trying to prevent: Extinction.