It would be understandable if my most recent stories make you feel disconnected from the consequences of Threatened species and species extinction. A northern European fungus and a small carnivorous plant, both of which have relatively small ranges and are not greatly used by humans, might seem insignificant. This week’s species is the opposite, with a broad range and a long history of human use. We’ll be talking about a fish that has driven economic growth in multiple countries for centuries. This is the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, which most of us have seen like the picture below as opposed to the one above.

The fish is native to coastal areas from north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina through Greenland, Iceland, Great Britain, the North and Baltic Seas, and areas of the Arctic Ocean. This animal and its consumption have driven economic fortunes and important historical events for some time. Many New England towns were created to take advantage of nearby cod fishing grounds.

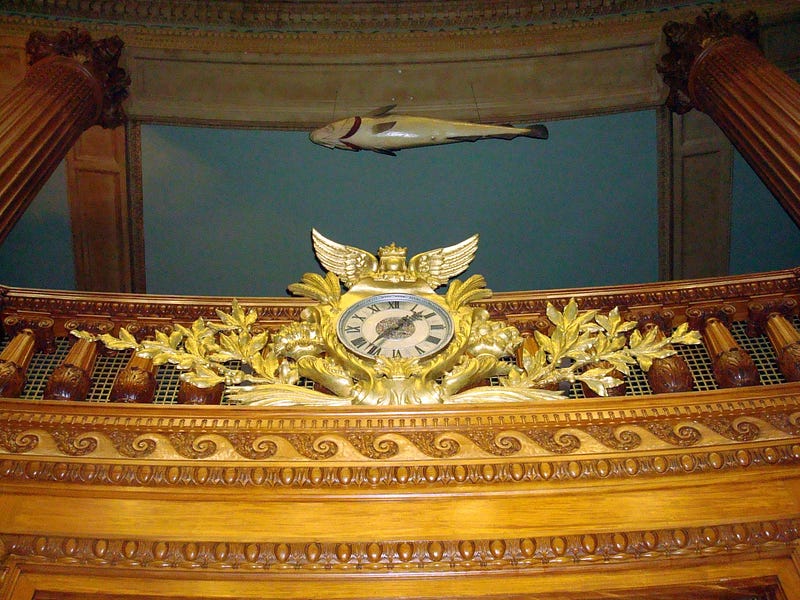

Salt cod was one of the commodities (and food sources) that helped drive the Atlantic slave trade. The British Molasses Act of 1733 was an attempt to control the trade between the colonies and the French Caribbean (including cod, but mainly to compete with cheap molasses), but was thwarted by a lucrative contraband agreement between the settlers and the French. As the Act was about to expire, the Sugar Act was passed in 1764. Bad feeling about this and various other taxes like the Stamp Act eventually led to the infamous Boston Tea Party protest. The importance of the fish to Massachusetts is commemorated in the State House of Representatives with a carving known as the ‘Sacred Cod’.

What happened to this important species? Overfishing. Technological advances allowed for more and more cod to be caught. These advances also caught many non-commercial fish, called bycatch, including important cod prey species. Furthermore, an all too frequent problem, called the Tragedy of the Commons, took place within the fishery. The long-term health of the cod population was important to society as a whole, but individuals benefited by catching as much cod as they could. When short term gains for individuals are at odds with long term success for all, a resource available to all can become overexploited and degraded.

In 1992, the northwest cod population fell off the edge of the proverbial knife blade. Total catch mass fell to 1% of its previous levels and the Canadian fisheries were closed. Since then, strict quotas have been put in place in order to help the fish stocks recover. Unfortunately, cod species as a whole do not seem to be quick to rebound from such devastating population size losses.

Currently, the Atlantic cod is classified as Vulnerable, having experienced significant population declines. The northwestern populations off the United States and Canada have been the hardest hit. The northeastern stocks have not been as severely exploited, which is why the species has not suffered declines sufficient to place it in a more serious category (Endangered or Critically Endangered). There is some recent evidence of recovery, but even 25 years after the initial collapse the fish stocks have still not fully replenished themselves. The future of the species is uncertain, especially if reckless overfishing practices return after the fish recover.

Next week, we’ll be continuing on to the next level of severity in the IUCN classification system: Endangered.