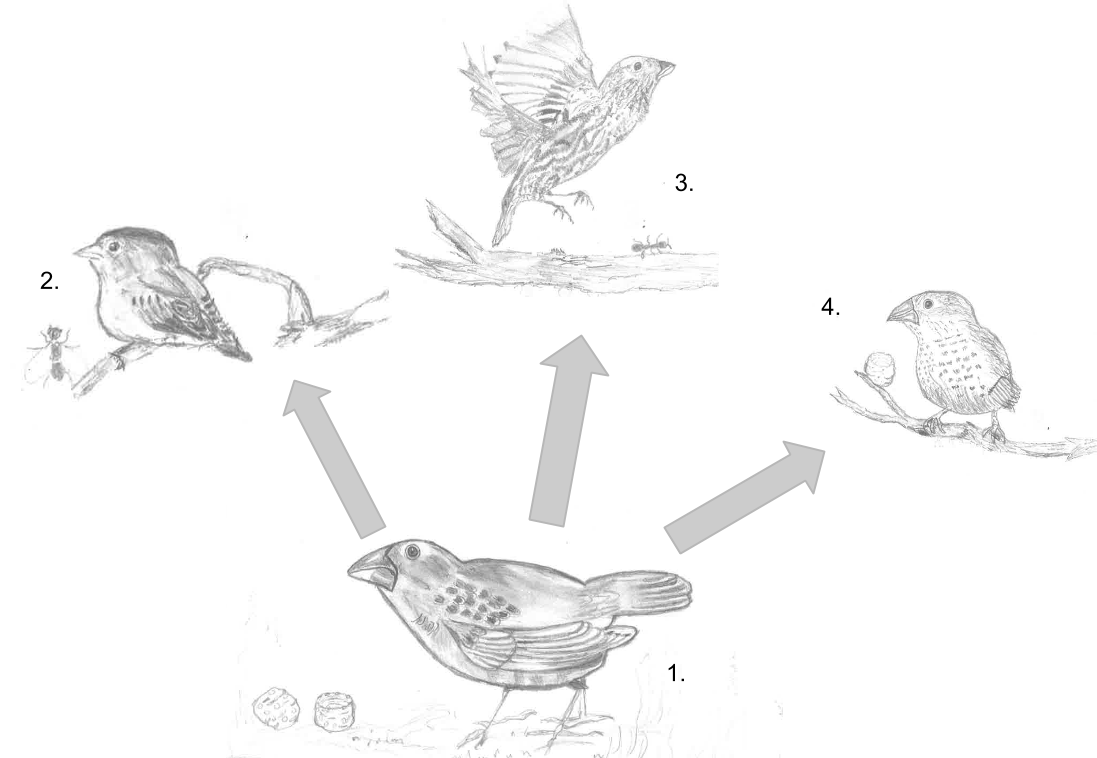

To start our season on foraging, I decided to use an example that I feel truly illustrates the variety that exists, as well as how the environment can be instrumental in shaping that variation. It’s a group of species that I’ve touched on briefly in one of my early stories, and again at the end of Season 2 when I talked about vampires. As you may be able to guess by the graphic above, I am referring to the Galápagos finches, commonly called Darwin’s finches.

These birds, actually members of the tanager family and not the finch family, arrived to the islands as a single species from the mainland sometime around two million years ago. Remote islands are an excellent ‘testing ground’ for evolution. The remoteness provides the requisite isolation as well as the availability of new niches for the incoming species to exploit.

As the ancestral bird spread throughout the islands, it found a wide variety of potential food sources that it could exploit. Those individuals with a beak shape suited for the new food source out-competed the others and so gradually different species began to diverge based on beak size and shape, eventually diversifying into 15 different species.

These include the ground finches (small, medium, and large) in the genus Geospiza. These three species are omnivores (omni is Latin for ‘all’ or ‘every’) meaning that they eat a variety of different foods. However, they have a preference for vegetable matter, including seeds, buds, flowers, and leaves. Their beak size correlates to the size of the seeds that they prefer, a larger,stronger beak being required in order to crack open large nuts.

That genus also includes that ‘vampire’ finch mention in Season 2 as well as a pair of cactus finches, which primarily feed on plants in the genus Opuntia, commonly known as the prickly pear cactus.

The tree finches (small, medium, and large), belong to the genus Camarhynchus, and are primarily insectivores. The beaks are grouped by size similarly to the ground finches and correspond to the size and type of insects consumed and where those prey can be found. The woodpecker finch, Camarhynchus pallidus, is well known for feeding on insects inside trees without a woodpecker’s sturdy bill or long tongue by relying on tools, usually a twig or cactus spine. Tool use for foraging is generally agreed to indicate high levels of intelligence.

The warbler-finches in the Certhidea genus fill the niche occupied by warblers on the mainland. They also eat insects, but are more able to pursue them on the wing rather than seeking them out in trees.

One of the more fascinating species is the vegetarian finch, Platyspiza crassirostris. It mainly consumes leaves, buds, and other plant matter. Its beak is shaped primarily for food manipulation rather than crushing like the ground finches. It can also use its beak to strip the bark off of twigs in order to get to the nutrients underneath.

These birds were able to develop this wide variety of feeding behaviors and beak morphology because of an overall lack of competition when the ancestral bird first reached the islands. Food niches that would normally be filled by other types of birds in a mainland ecosystem were free and open for exploitation. The characteristics of each island were slightly different, meaning that many similar species of the 15 do not overlap on the same islands.

The feeding mechanisms (the beak) slowly changed to suit the new niches and the feeding behaviors changed to suit the new forms. It is also important to understand that these changes are not static, but ongoing. There is documented evidence in recent history of changes in the beak size of the medium ground finch, Geospiza fortis. This species preferred smaller, softer seeds, but a severe drought in the islands drove this species to resort to consuming seeds that were larger and harder to crack than its normal fare. Within a few generations, average beak size had already changed by 10%.

I consider these birds to be an excellent introduction to this season on foraging and diet, because they show how just small changes can accumulate over time until the foraging habits and structures of two closely related species can completely diverge. It also shows the importance of environment on these behaviors and structures. Keep this in mind as we continue with some of the more interesting and exotic examples of foraging throughout Season 5.

Thank you all for reading. I hope you enjoy my stories. If you do, please consider sharing this with others and spreading the word. I’m also always interested in what kinds of topics my readers are interested in learning about, so let me know if you have an idea or suggestion for future seasons.